Experience Matters: Improving the Quality of Health Care Through a Focus on Family and Child Perspectives

Published on February 9, 2024

By Kate Gilroy with contributions from Maia Johnstone, Reshma Naik, Soumya Alva, and Lara Vaz, MOMENTUM Knowledge Accelerator

This blog is part of a series on patient experience of care. It highlights insights, reflections, and resources related to pediatric experience of care. Visit the MOMENTUM website to read the other blogs and learn more about how insights from MOMENTUM’s experience of care work may apply to your work.

Global mortality among children under age 5 has decreased remarkably over the last few decades, but every year, approximately 5 million children ages 0 to 5 still die.1 After the newborn period (0 to 28 days), many children ages 1 month to 59 months die from preventable and treatable illnesses such as lower respiratory infections, malaria, and diarrhea.2 Preventing and treating these illnesses and, consequently, reducing child morbidity and mortality, requires families to seek care within the health system, usually at health facilities, and facilities to provide high-quality care.

High-quality pediatric care, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), involves providing children ages 0 to 15 with the right clinical interventions to prevent or treat their illnesses. It also involves communicating effectively with children, their caretakers, and families; respecting their rights; empowering them to meaningfully participate in the care; and offering appropriate emotional and psychological support.

What might this care look like in practice? As any parent knows, young children need many visits to the primary care clinic for their checkups, vaccines, and the latest illness that’s circulating in the community. During these visits, children can be prodded, poked, put on cold scales, and talked about by providers like they aren’t even present. But when doctors and nurses communicate and engage with children and their families in kind, open, and respectful ways, and provide support to anticipate and meet their needs, it helps build families’ trust and confidence in the health care system.

When caregivers feel confident in the care they and their children receive, they are much more likely to return for their children’s future health care needs and even for their own. In contrast, if health care providers are disrespectful, for example shouting or blaming a mother for “letting” her child get sick, that experience might affect her future decisions about where and when to seek care for her children. Her experience could even deter or delay other family members from seeking the care they need.

The WHO’s quality-of-care (QoC) standards for children were released in 2018, and a core set of pediatric quality indicators followed in 2022. However, researchers and program managers still have limited guidance on how best to apply conceptual frameworks and measures to assess how children, their caregivers, and families experience health care in low- and middle-income settings.3 At the same time, program managers in specific fields of child health, such as immunization, increasingly recognize that ensuring children and families have positive experiences when receiving services is essential to meeting their goals. Positive experiences greatly improve the chances of repeat visits for children to receive their full set of vaccinations and be protected from death and illness due to preventable diseases.4 However, standard metrics of the immunization service experience to prioritize actions and monitor progress are yet to be developed, defined, and tested.5

What is Unique About Pediatric Experience of Care?

Improving pediatric experience of care is distinct from improving respectful maternity services or experience of care for other populations because we’re often talking about a caregiver’s or family’s experience in addition to that of the child’s experience. Health care providers of young children most often communicate with caregivers, who interpret the child’s symptoms and responses and are responsible for consenting to care. But it is also important for providers to treat and communicate with children directly in age- and culturally appropriate ways.

When it comes to measurement, most existing tools ask caregivers—usually mothers—about their experiences; few tools capture the experience of care from children’s points of view, especially younger children. Adding further complexity, it is common for several family members to be involved in the care of children at different points in time, and they all may have different expectations and levels of understanding. Thus, ensuring consistently positive experiences of care and measuring them adequately can be challenging.

Context can also affect how children’s and caregivers’ experiences of care play out. In settings with especially high rates of child death and illness, health care staff are often focused on moving quickly to triage many patients and address emergencies to ensure survival. These pressures leave them with less time and mental energy to explain or nurture the caregiver-child pair. When facilities are also chronically understaffed and underfunded, promoting positive pediatric experience of care can be seen as a luxury.6

Moving the Needle: Research and Programming from MOMENTUM

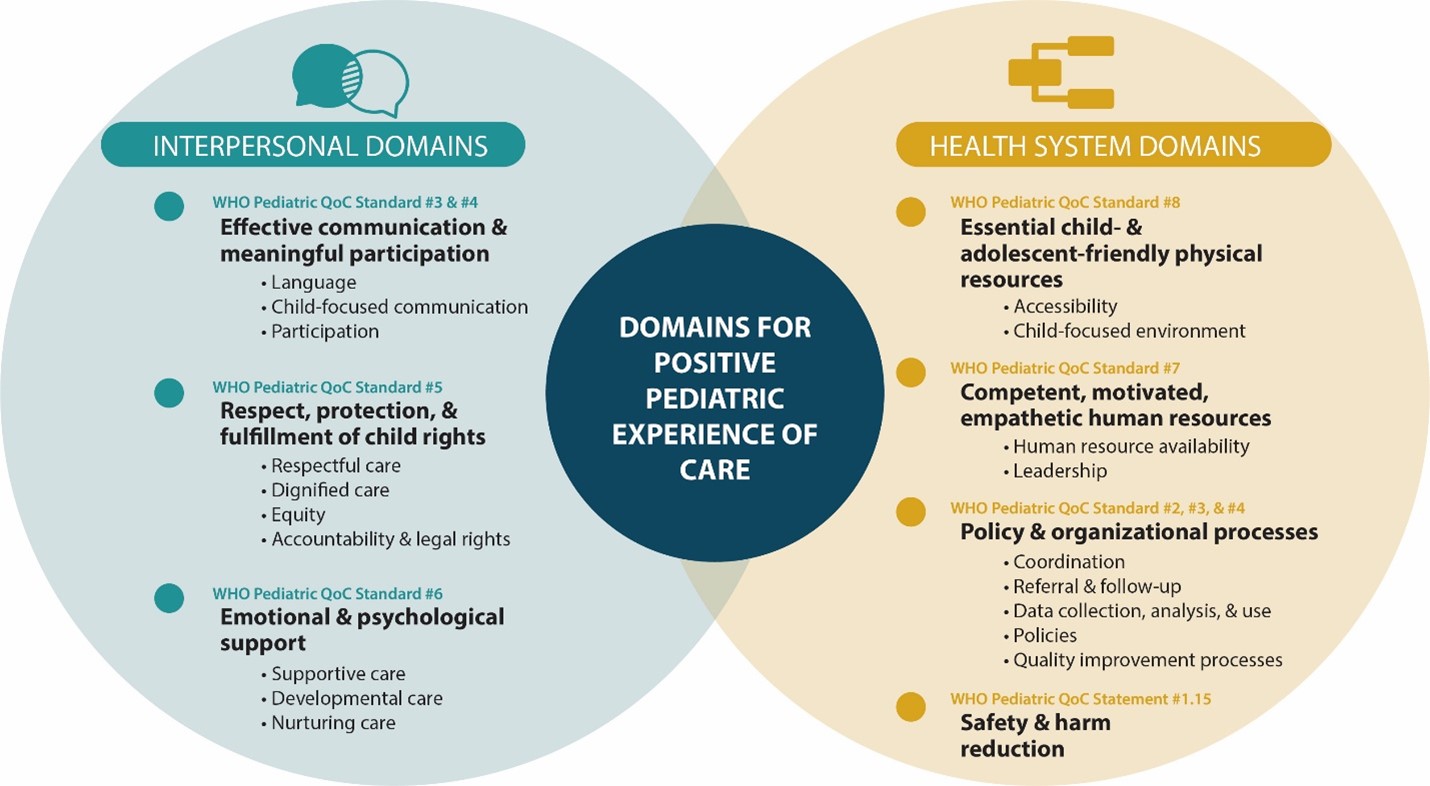

MOMENTUM conducted a landscape review that builds on the WHO’s quality standards for children to further identify what factors contribute to positive and negative experiences of care and identify gaps for additional exploration.3 One of the review’s key outcomes is a proposed framework that highlights aspects of interpersonal interactions and the health system—also called domains—that comprise positive pediatric experience of care (see figure).

The interpersonal domains include child-focused communication appropriate for the child’s age and developmental stage, as well as provider-client interactions that are private, confidential, and free from prejudice, humiliation, and blame. For example, providers should recognize that even young children have rights and speak with them in language they can understand, including using cards with imagery to communicate. Importantly, children should be given space to express how they’re feeling about their health care experience. Emotional and psychological support for children and their families is especially important when they are dealing with painful symptoms, unknown or prolonged illnesses, or distressing diagnoses. Children typically receive support and comfort from their family members and caregivers; thus, families should be allowed to be with children as much as possible during medical procedures and contact with health care providers.

At the health systems level, health facilities’ infrastructure, equipment, and supplies should be accessible to children and their families, including those with various types of physical, congenital, and developmental disabilities. For example, hygiene facilities should be child- and family-friendly, with proper pediatric medication formulas and doses in stock. Competent, motivated, and empathetic health care providers are essential for ensuring positive patient-provider interactions and overall experience of care—for everyone. Ongoing efforts to understand and improve health care providers’ experiences in delivering services will contribute to improvements in patients’ and families’ engagements with providers and the health system.7 Importantly, providers deserve to work in supportive environments, with policies and organizational processes that bolster their own, as well as children’s and families’, positive experiences and promote overall high-quality care.

The landscape review found that:

- No single measurement tool or metric currently encompasses every aspect defined in the proposed framework.

- Most metrics that address the interpersonal domains focus on emotions, such as feelings about providers’ level of friendliness or kindness, and overall satisfaction levels.

- Only some tools focus on the specific interpersonal and communication needs of children and their families. Few existing metrics assess consent, children’s rights, or accountability and legal rights.

- Many tools are designed for chronically ill children; only a few tools focus on routine, well-child, or outpatient-child health care.

- Most tools solicit feedback from caregivers. Few tools use direct observations of children or age-appropriate questions targeted at children; very few ask questions to draw out an understanding of children’s points of view.

- Most identified tools involve intensive implementation efforts with independent, external observers or interviewers; no tools were designed for use within routine health information systems.

What More is Needed?

To improve the quality of child health care, it will be important to: promote implementation approaches to ensure children and their families have positive pediatric experiences of care; develop more robust ways to measure the pediatric experience of care; and use emerging data to plan programs, track progress, and adjust over time.

Global, regional, and country stakeholders can take an important first step by elevating the notion that positive pediatric experience of care is a key aspect of high-quality services and responsive primary health care. Program managers should introduce and enhance quality improvement approaches that promote families’ positive experiences, such as ensuring health facilities have adequate resources, staffing, and support so that health care providers are enabled, empowered, and encouraged to interact with parents and children in a respectful and responsive manner. Children and families’ positive experiences, combined with high-quality clinical care, can contribute to population health, as satisfied families are more likely to follow providers’ advice about how to manage and treat children at home and return to use various health services when needed.

Stakeholders can also strongly advocate for pediatric experience of care to be measured and monitored over time. These measures should address health system factors such as infrastructure and institutional policies, and the availability of necessary support to health care providers that enables positive interactions and experiences between children and their families and creates a positive working environment for health care providers. Researchers can help fill key information gaps by implementing formative and qualitative research studies in different clinical and cultural contexts to understand experience of care from the varied perspectives of children, caretakers, families, and health care providers.

More research is also needed to better understand the complex interactions between interpersonal interactions and the health system, including health care providers’ perspectives and the structures that can support them. Finally, as the field progresses and new metrics for the pediatric experience of care are developed, they will need to be integrated and tested within existing health information systems to identify necessary adjustments and routinely monitor progress.

To learn more about patient experience of care, check out these useful resources:

- Standards for Improving the Quality of Care for Children and Young Adolescents in Health Facilities

- Improving Metrics and Methods for Assessing Experience of Care Among Children and Caregivers in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

References

- United Nations Interagency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. (2023). Levels & trends in child mortality: Report 2022, Estimates developed by the United Nations Inter-agency Group of Child Mortality Estimation. New York, NY: United Nations Children’s Fund.

- Villavicencio, F., Perin, J., Eilerts-Spinelli, H., Yeung, D., Prieto-Merino, D., Hug, L., Sharrow, D., You, D., Strong, K.L., Black, R.E. and Liu, L. (2024). Global, regional, and national causes of death in children and adolescents younger than 20 years: an open data portal with estimates for 2000–21. The Lancet Global Health, 12(1), e16-e17.

- Sacks, E., Silla, N., Cernigliario, D., and Gilroy, K. (2023). Improving metrics and methods for assessing experience of care among children and caregivers in low- and middle-income countries. Washington, DC: USAID MOMENTUM Knowledge Accelerator.

- The UNICEF Journey to Health and Immunization framework. UNICEF, Demand for health services field guide: a human-centered approach. New York: UNICEF, 2018. https://demandhub.org/service-experience/

- Budden, A. Synthesis of immunization service experience interventions and monitoring and measurement approaches for zero-dose and under-immunized children. The Task Force for Global Health.

- World Health Organization, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and The World Bank. (2018). Delivering quality health services: A global imperative for universal health coverage.

- Afulani, P.A., Oboke, E.N., Ogolla, B.A., Getahun, M., Kinyua, J., Olouch, I., and Ongeri, L. (2023). Caring for providers to improve patient experience (CPIPE): Intervention development process. Global Health Action 16:1.